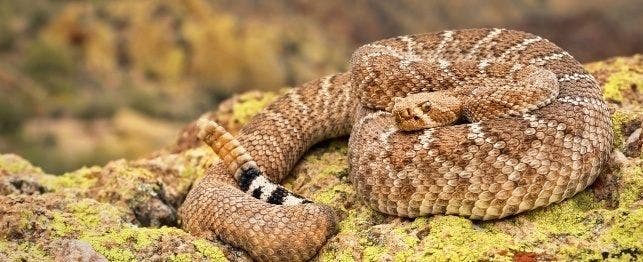

Rattlesnake Born of a Virgin

BOULDER, Colo. – Young male celebrity, a little on the wild side but comfortable in an academic setting, seeks like-minded female for long-term relationship. Turn-ons: rats and mice, dead tree stumps and long walks, er, slithers in the woods. Potential partner must be willing to relocate, and must be from the right family. If only finding a girlfriend for Napoleon were that easy, David Chiszar would have arranged things by now.

As it is, the whole herpetological world is holding its collective breath, waiting to see if Napoleon – a timber rattlesnake whose birth three years ago stunned snake scholars – can father babies of his own. If he does, this would be a first. There are no known cases of snakes conceived in this manner, having offspring. Moreover, it would represent a form a cloning in nature.

“His time just hasn’t come yet,” says Chiszar, a professor of psychology at the University of Colorado and an expert in snake behavior. “I need a girl snake and I don’t have one for him. Now, if I were in timber rattlesnake country, it would be different. But this is prairie rattlesnake country.”

Besides, notes Chiszar, Napoleon’s sex life just hasn’t been his top priority up until now. “But,” he says, now that Napoleon has reached the age of sexual maturity, “I reckon I’ll be takin’ a trip to Georgia to catch one.”

Napoleon entered the world completely unexpectedly in 1995. His mother, then a 14-year-old, 3-foot timber rattler named Marsha Joan, had lived virtually her entire life chastely in her cage in Chiszar’s research lab. She was a virgin snake. Chiszar, who chaperoned her since she was two days old, vouches for that.

Yet one morning Chiszar entered the lab, and there was newborn Napoleon. His birth is one of just a handful of documented cases of virgin birth – parthenogenesis – among snakes.

“We don’t know for sure how she pulled that off,” says Chiszar, who keeps more than 100 slithery beasts as subjects for his research into snakes’ sensory mechanisms. “I’m confident she was never with a boy, because I never put a boy in her cage and I never put her in a boy’s cage. But she hauled off and had a baby.”

DNA testing of both snakes’ blood confirms that Napoleon is nearly an exact genetic copy of his mother. No father snake contributed genetic material to the feisty 5-year-old.

Parthenogenesis is standard reproductive procedure in a number of animals, including several species of fish, lizards and frogs. It’s even been documented in turkeys, through artificial means. But in the snake world, Papa Snake makes an important contribution to the next generation. Until recently, parthenogenesis had been reported – though never confirmed through DNA testing – in only one species, the Brahminy blind snake.

Chiszar and his colleagues have since been able to identify three other female snakes besides Marsha Joan that produced fatherless babies: a wandering garter snake at the University of Arizona, an Aruba island rattlesnake at the Toledo, Ohio, zoo; and a checkered garter snake at the Phoenix Zoo. There are also reports that an Australian swimming filesnake at Chicago’s Brookfield Zoo did it, and a lizard – an Argentina chuckwalla – living with an elderly woman who was keeping it for her grandson in Greeley, Colo., did too.

All but one of the snakes were older mothers who had lived many years without male companionship. All the offspring were male.

A bit of genetic background: In humans, females carry two X chromosomes, while males have an X and a Y chromosome. In snakes, the reverse is true. Chiszar and other scientists speculate that baby snakes born through parthenogenesis are the product of the mother’s duplicating her own chromosomes in the place of the missing father’s, thereby self-fertilizing her egg. This would lead to embryos with either XX or YY sex chromosomes – and YYs don’t live. Scientists don’t think it’s possible for a snake to produce offspring with an X and a Y chromosome – that is, a female – through parthenogenesis.

But then again, they’re not even sure about that. Maybe some snake somewhere has, and it’s just never been reported. Chiszar says it’s possible that parthenogenesis accounts for more births than believed. In captivity, few snakes are kept alone; zoos typically pair their animals. “Even if this had occurred many times, it’s likely zookeepers would have missed it, thinking it was normal birth inspired by sexual relations,” Chiszar says.

Also, female reptiles have an amazing ability to store sperm for long periods, then use it to fertilize their eggs at a propitious time. “The record is seven years,” Chiszar says. Thus, even when a captive female that has spent years without a mate gives birth, keepers routinely credit long-term sperm storage. “Maybe some of those cases weren’t due to long-term storage,” Chiszar says.

Marsha Joan died quietly of old age earlier this summer, Chiszar says. Only once her son meets a nice female timber rattler will Chiszar know whether he is fertile. If he’s not, his birth could be nothing more than an insignificant misfiring of his mother’s reproductive system, a freak of nature. If he is fertile, Chiszar and the other researchers may be witnessing a previously unknown adaptive skill in snakes.

“We don’t know how common this is in nature,” Chiszar says. “The fact that it occurs in captivity tells me it probably occurs in nature too – but having that view and demonstrating it are two different things.”

Chiszar says Napoleon will probably undergo more blood tests for genetic analysis. But other than that, Napoleon’s only job around the lab is just to keep growing and preparing himself for the day Chiszar finally introduces him to some pretty little female rattler.